Indholdsfortegnelse

Richard Trevithick (13. april 1771 - 22. april 1833). Britisk opfinder og mineingeniør. Hans største succes var højtryksdampmaskinen og han byggede også det første funktionsduelige damplokomotiv.

Richard Trevithick (13. april 1771 - 22. april 1833). Britisk opfinder og mineingeniør. Hans største succes var højtryksdampmaskinen og han byggede også det første funktionsduelige damplokomotiv.

Childhood and early life

Richard blev født i Tregajorran (i Illogan sogn), mellem Camborne og Redruth, i hjertet af et af Cornwalls mineralrige mineområder. Han var den yngste og den eneste dreng i en familie med 6 børn. He was very tall and athletic and concentrated more on sport than schoolwork. He was sent to the village elementary school at Camborne and evidently did not take much advantage of the education provided, with the exception of arithmetic, for which he had an aptitude. One of his school masters described him as 'a disobedient, slow, obstinate, spoiled boy, frequently absent and very inattentive'.<ref> Hodge, James; Richard Trevithick, Lifelines 6 (2003); Shire Publications Ltd, Risborough, Buckinghamshire HP27 9AA UK; p11</ref>

Trevithick var søn af en mine 'kaptajn', Richard Trevithick (1735-1797), og datteren af en minearbejder Ann Teague (?-1810), og som barn kunne han iagttage dampmaskiner pumpe vand op fra de dybe tin- og kobberminer common in Cornwall. For a time he was a neighbour to William Murdoch, the steam carriage pioneer, and would have been influenced by his experiments with steam powered road locomotion.<ref>Griffiths, John C (2004), 'William Murdock', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.</ref> Until that time, such steam engines were of the condensing or atmospheric type, originally invented by Thomas Newcomen in 1712, and which also became known as low pressure engines. James Watt, on behalf of his partnership with Matthew Boulton, Boulton & Watt, held a number of patents for improving the efficiency of Newcomen’s engine, including the ‘separate condenser patent’ which proved to be the most contentious.

Trevithick's first job, at the age of 19, was at the East Stray Park Mine. He was very enthusiastic and quickly gained the status as a consultant, unusual for a person at such a young age. He was popular with the miners because of the respect they had for his father. He worked on building and modifying steam engines to avoid the royalties due to Watt on the separate condenser patent. Another of his projects was the plunger pole pump, a type of pump used with a beam engine and used widely in Cornwall's tin mines, in which he reversed the plunger to change it into a water-power engine.

Familie

I 1797 giftede Trevithick sig med Jane Harvey fra Hayle. Jane var datter af John Harvey (ironfounder), tidligere smed fra Carnhell Green der etablerede et lokalt jernstøberi Harveys of Hayle. Selskabet blev berømt over hele verden for at bygge store stationære 'beam' engines til oppumpning af vand, som regel fra minerne. Maskinerne var baseret på Newcomen’s og Watt’s maskiner.

De fik børnene

- Richard Trevithick (1798-1872);

- Anne Ellis (1800-1876);

- Elizabeth Banfield (1803-1870);

- John Harvey Trevithick (1807-1877);

- Francis Trevithick (1812-1877); og

- Frederick Henry Trevithick (1816-1881)

The high pressure engine

Efterhånden som han blev mere erfaren forstod han, at forbedringerne i teknikken til at bygge kedler muliggjorde sikker produktion af damp med højt tryk og at dette kunne anvendes direkte til at bevæge et stempel i en dampmaskine i stedte for som hidtil at benytte den ene atmosfære i kondenserende maskiner.

He was not the first to think of so-called „strong steam“. William Murdoch had developed and demonstrated a model steam carriage, starting in 1784, and demonstrated it to Trevithick at his request in 1794. In fact, Trevithick lived next door to Murdoch in 1798 and 1799.

However, Trevithick was the first to make high pressure steam work, in 1799. Not only would a high pressure steam engine eliminate the condenser but it would allow the use of a smaller cylinder, thus saving space and weight. He reasoned that his engine could now be more compact, lighter and small enough to carry its own weight even with a carriage attached. (Note this did not use the expansion of the steam, so-called „expansive working“ came later).

He started building his first models of high pressure (meaning a few atmospheres) steam engines, initially a stationary one and then one attached to a road carriage. Exhaust steam was vented via a vertical pipe or chimney straight into the atmosphere, thus avoiding a condenser and any possible infringements of Watt's patent. The linear motion was directly converted into circular motion via a crank instead of using an inefficient beam.

The Puffing Devil

Trevithick built a full-size steam road locomotive in 1801 on a site near the present day Fore Street at Camborne, which was also known as

Trevithick built a full-size steam road locomotive in 1801 on a site near the present day Fore Street at Camborne, which was also known as Camborne Hill. He named the carriage 'Puffing Devil' and, on Christmas Eve that year, he demonstrated it by successfully carrying several men up Camborne Hill and then continuing on to the nearby village of Beacon with his cousin and associate, Andrew Vivian, steering. This event is believed by many to be the first demonstration of transportation by (steam) auto-motive power and it later inspired the popular Cornish folk song „Camborne Hill“. However, others suggest that Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot may have an earlier claim with his steam wagon of 1770, or even that a steam powered car built in 1672 by Ferdinand Verbiest was the first steam-powered vehicle.<ref>title=SA MOTORING HISTORY - TIMELINE

|publisher=Government of South Australia

|url=http://www.history.sa.gov.au/motor/education/sa_motor_history.pdf

</ref><ref>author=Setright, L. J. K.

|title=Drive On!: A Social History of the Motor Car

|publisher=Granta Books

|year=2004

|id=ISBN 1-86207-698-7

</ref> During further tests, Trevithick's locomotive broke down 3 days later, after passing over a gully in the road. The vehicle was left under some shelter with the fire still burning whilst the operators retired to a nearby public house for a meal of roast goose and drinks. Meanwhile the water boiled off, the engine overheated and the whole machine burnt out, completely destroying it. Trevithick however did not consider this episode a serious setback but more a case of operator error.

In 1802 Trevithick took out a patent for his high pressure steam engine.<ref>Rogers, Col. H. C. Turnpike to Iron Road (Seeley, Service & Co. Ltd. London 1961), pp 40 - 44.</ref>

Anxious to prove his ideas, he built a stationary engine at the Coalbrookdale Company's works in Shropshire in 1802, forcing water to a measured height to measure the work done. The engine ran at forty piston strokes a minute, with an unprecedented boiler pressure of 145 psi. The company then built a rail locomotive for him, but little is known about it, including whether or not it actually ran. To date the only known information about it comes from a drawing preserved at the Science Museum, London, and a letter written by Trevithick to his friend, Davies Giddy. This is the drawing used as the basis of all images and replicas of the later Penydarren locomotive, as no plans for that locomotive have survived.

The London Steam Carriage

The Puffing Devil was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods, so in fact would have been of little practical use. In 1803 he built another steam-powered road vehicle called the

The Puffing Devil was unable to maintain sufficient steam pressure for long periods, so in fact would have been of little practical use. In 1803 he built another steam-powered road vehicle called the London Steam Carriage, which attracted much attention from the public and press when he drove it that year in London from Holborn to Paddington and back. However, it was particularly uncomfortable for passengers and proved more expensive to run than a conventional horse-drawn carriage and so was abandoned.

The tragedy at Greenwich

Også i 1803, eksploderede en af Trevithick's stationære pumpemaskiner, der blev benyttet i Greenwich, herved omkom 4 personer. Although Trevithick considered the explosion was caused by another case of careless operation rather than design error, the incident was exploited relentlessly by his competitors and promoters of the low-pressure engine, Watt and Boulton, who highlighted the perceived risks of using high pressure steam. Trevithick's response was to incorporate two safety valves into future designs, only one of which could be adjusted by the operator.<ref>Kirkby, R. S. et al., Engineering in History, pp 175 - 177. ISBN 0-486-26412-2.</ref> The adjustable valve comprised a disk covering a small hole at the top of the boiler above the water level in the steam chest. The force exerted by the steam pressure was equalised by an opposite force created by a weight attached to a pivoted lever. The position of the weight on the lever was adjustable thus allowing the operator to set the maximum steam pressure. The second valve was in fact a lead plug critically positioned in the boiler just below the minimum safe water level. Under normal operation the water temperature could not exceed that of boiling water and therefore kept the lead below its melting point. In the event of the water running low, once it had exposed the lead plug the cooling effect of the water was lost and the temperature could rise sufficiently to melt the lead. This would release steam into the atmosphere, reduce the boiler pressure and provide an audible alarm in sufficient time for the operator to damp down the fire and let the boiler cool naturally before any permanent damage could occur.

The world's first railway locomotive

In 1802 Trevithick built one of his high pressure steam engines to drive an automatic hammer at the Pen-y-Darren iron works near Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales. With the assistance of Rees Jones, an employee of the iron works and under the supervision of Samuel Homfray, the proprietor, he mounted the engine on wheels and turned it into a locomotive. In 1803 Trevithick sold the patents for his locomotives to Samuel Homfray.

Homfray was so impressed with Trevithick's locomotive that he made a bet with another ironmaster, Richard Crawshay, for 500 guineas that Trevithick's steam locomotive could haul 10 tons of iron along the Merthyr Tydfil Tramroad from Penydarren to Abercynon, a distance of 9.75 miles (16 km). Amid great interest from the public, on 21 February 1804 it successfully carried 10 tons of iron, 5 wagons and 70 men the full distance in 4 hours and 5 minutes, an average speed of nearly 5|mi/h|km/h|abbr=on.<ref>author=Rattenbury, Gordon|coauthors=Lewis, M. J. T.|title=Merthyr Tydfil Tramroads and their Locomotives|year=2004|publisher=Railway & Canal Historical Society|location=Oxford|isbn=0-901461-52-0</ref> As well as Homfray, Crawshay and the passengers, other witnesses included Mr. Giddy, a respected patron of Trevithick and an 'engineer from the Government'.<ref>Rogers, Colonel H. C. OBE, op. cit., pp 40</ref> The engineer from the Government was probably a safety inspector and particularly interested in the boiler's ability to withstand high steam pressures.

The locomotive itself was of a very primitive design. It comprised a boiler mounted upon a four wheel frame. At one end, a single cylinder with very long stroke was mounted partly in the boiler, and a piston rod crosshead ran out along a slidebar, an arrangement that looked like a giant trombone. As there was only one power stroke, this was coupled to a large flywheel mounted on one side. The rotational inertia of the flywheel would even out the movement that was transmitted to a central cog-wheel that was, in turn connected to the driving wheels. It again used a high pressure cylinder without a condenser, the exhaust steam being used to assist the draught via the firebox, increasing efficiency even more. These fundamental improvements in steam engine designs by Trevithick did not change for the whole of the steam era.

The bet was won. Despite many people's doubts, it had been shown that, provided that the gradient was sufficiently shallow, it was possible to successfully haul heavy carriages along a "smooth" iron road using the adhesive weight alone of a suitably heavy and powerful steam locomotive. Trevithick's was probably the first to do so;<ref>Kirkby, R. S., et al. op. cit., pp 274 - 275</ref> however some of the short cast iron plates of the tramroad broke under the locomotive as they were intended only to support the lighter axle load of horse-drawn wagons and so the tramroad returned to horse power after the initial test run.

Homfray was pleased enough. He had won his bet and the engine was placed on blocks and reverted to its original stationary job of driving the hammers. Hearing of the success in Wales, Christopher Blackett, proprietor of the Wylam colliery near Newcastle wrote to Trevithick asking for locomotive designs. These were sent to John Whitfield at Gateshead, Trevithick's agent, who built what was to be Trevithick's second locomotive. Blackett was using wooden rails for his tramway and, once again, Trevithick's machine was to prove too heavy for its track.1)

In London

Tunnelling under the Thames

I 1805 blev Robert Vazie, another Cornish engineer, af Thames Archway Company valgt til at bygge en tunnel under Thremsen ved Rotherhithe. Vazie encountered serious problems with water influx and got no further than sinking the end shafts when the directors called in Trevithick for consultation. The directors agreed to pay Trevithick £1000 if he could successfully complete the tunnel, a length of 1220 feet (366 m). In August 1807 Trevithick began driving a small tunnel 5 feet (1.5 m) high tapering from 2 feet 6 inches (0.75 m) at the top to 3 feet (0.9 m) at the bottom. By 23 December after it had progressed 950 feet (285 m) progress was delayed after a sudden inrush of water and only one month later, at 1040 feet (312 m), a more serious inrush occurred. The tunnel was flooded and Trevithick, being the last to leave, was nearly drowned. Progress stalled and a few of the directors attempted to discredit Trevithick but the quality of his work was eventually upheld by two colliery engineers from the North of England. Despite suggesting various building techniques to complete the project, including a submerged cast iron tube, Trevithick's links with the company ceased and the project was never actually completed. The first successful tunnel under the Thames would be started by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel in 1823, three quarters of a mile upstream, assisted by his son Isambard Kingdom Brunel (who also nearly died in a tunnel collapse). Marc Brunel finally completed it in 1843, the delays being due to problems with funding. However, Trevithick's suggestion of a submerged tube approach was successfully implemented for the first time across the Detroit River in Michigan with the construction of the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel, under the engineering supervision of the The New York Central Railway's engineering vice president, William J. Wilgus. Construction began in 1903 and was completed in 1910. The Detroit–Windsor Tunnel which was completed in 1930 for automotive traffic, and the tunnel under the Hong Kong harbour were also submerged tube designs.

"Catch Me Who Can"

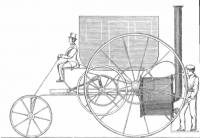

thumb|Trevithick's steam circus

In 1808 Trevithick publicised his steam railway locomotive expertise by building a new locomotive called 'Catch me who can', built for him by John Hazledine and John Urpeth Rastrick at Bridgnorth in Shropshire, similar to that used at Penydarren and named by Mr. Giddy's daughter. This was probably Trevithick's third railway locomotive after those used at Penydarren ironworks and the Wylam colliery. He ran it on a circular track south of the present day Euston Station in London, whose site in Bloomsbury has recently been identified archaeologically as that occupied by the ''Chadwick Building'', part of University College London.<ref>Tyler, N., 'Trevithick's Circle' Trans. Newcomen Soc. 77 (2007), 101-13. </ref> Admission to the „steam circus“ was one shilling including a ride and it was intended to show that rail travel was faster than by horse. This venture also suffered from weak tracks and the interest from the public was limited. Trevithick was disappointed by the response and designed no more railway locomotives. It was not until 1812 that twin cylinder steam locomotives, built by Matthew Murray in Holbeck, successfully started replacing horses for hauling coal wagons on the edge railed Middleton Railway from Middleton colliery to Leeds, West Yorkshire.

Trevithick went on to research other projects to exploit his high pressure steam engines: boring brass for cannon manufacture, stone crushing, rolling mills, forge hammers, blast furnace blowers as well as the traditional mining applications. He also built a barge powered by paddle wheels and several dredgers.

Trevithick saw opportunities in London and persuaded his wife and 4 children reluctantly to join him in 1808 for two and a half years lodging first in Rotherhithe and then in Limehouse.

Nautical projects

In 1808 Trevithick entered a partnership with Robert Dickinson, a West India merchant. Dickinson supported several of Trevithick's patents. The first of these was the 'Nautical Labourer'; a steam tug with a floating crane propelled by paddle wheels. However it did not meet the fire regulations for the docks and the Society of Coal Whippers, worried about losing their livelihood, even threatened the life of Trevithick.

Another patent was for the installation of iron tanks in ships for storage of cargo and water instead of in wooden casks. A small works was set up at Limehouse to manufacture them, employing 3 men. The tanks were also used to raise sunken wrecks by placing them under the wreck and creating buoyancy by pumping them full of air. In 1810 a wreck near Margate was raised in this way but there was a dispute over payment and Trevithick was driven to cut the lashings loose and let it sink again.

In 1809 Trevithick worked on various ideas on improvements for ships: iron floating docks, iron ships, telescopic iron masts, improved ship structures, iron buoys and using heat from the ships boilers for cooking.

Failure

In May 1810 he caught typhoid and nearly died. By September he had recovered sufficiently to travel back to Cornwall by ship and in February 1811 he and Dickinson were declared bankrupt. They were not discharged until 1814, Trevithick having paid off most of the partnership debts from his own funds.

Back in Cornwall

The Cornish boiler and the Cornish engine

In about 1812 Trevithick designed the ‘Cornish boiler’. These were horizontal, cylindrical boilers with internal sealed fire tubes passing horizontally through the middle. Hot exhaust gasses from the fire passed through the tubes thus increasing the surface area heating the water and improving efficiency. These types were installed in the Boulton and Watt pumping engines at Dolcoath and more than doubled their efficiency.

Again in 1812 he installed a new 'high pressure' experimental steam engine also with condensing at Wheal Prosper. This became known as the 'Cornish engine' and was the most efficient in the world at that time. Other Cornish engineers contributed to its development but Trevithick's work was predominant. In the same year he installed another high pressure engine, though non-condensing, in a threshing machine on a farm at Probus, Cornwall. It was very successful and proved to be cheaper to run than the horses it replaced. It ran for 70 years and was then exhibited at the Science Museum.

The recoil engine

In one of Trevithick’s more unusual projects, he attempted to build a 'recoil engine' based on the famous model built by Hero of Alexandria in about AD 50. This comprised a boiler feeding a hollow axle to route the steam to a catherine wheel with 2 fine bore steam jets on its circumference, the first 15|ft|m in diameter and a later model 24|ft|m in diameter. To get any usable torque, steam had to issue from the nozzles at very high velocity and in large volumes and it proved not to operate with adequate efficiency.

South America

Draining the Peruvian silver mines

In 1811 draining water from the rich silver mines of Cerro de Pasco in Peru at an altitude of 14,000 feet (4267 m) posed serious problems for the man in charge, Francisco Uville. The low pressure condensing engines by Boulton and Watt developed so little power as to be useless at this altitude, and they could not be dismantled into sufficiently small pieces to be transported there along mule tracks. Uville was sent to England to investigate using Trevithick's high pressure steam engine. He bought one for 20 guineas, transported it back and found it to work quite satisfactorily. In 1813 Uville set sail again for England and, having fallen ill on the way, broke his journey via Jamaica. When he had recovered he boarded the Falmouth packet ship 'Fox' coincidentally with one of Trevithick's cousins on board the same vessel. Trevithick's home was just a few miles from Falmouth so Uville was able to meet him and tell him about the project.

Trevithick leaves for South America

On 20 October 1816 Trevithick left Penzance on the whaler ship Asp accompanied by a lawyer Page and a boilermaker bound for Peru. He was received by Uville with honour initially but relations soon broke down and Trevithick left in disgust at the accusations directed at him. He travelled widely in Peru acting as a consultant on mining methods. The government granted him certain mining rights and he found mining areas, but did not have the funds to develop them, with the exception of a copper and silver mine at Caxatambo. After a time serving in the army of Simon Bolivar he returned to Caxatambo but due to the unsettled state of the country and presence of the Spanish army he was forced to leave the area and abandon £5000 worth of ore ready to ship. Uville died in 1818 and Trevithick soon returned to Cerro de Pasco to continue mining. However the war of liberation denied him several objectives. Meanwhile, back in England, he was accused of neglecting his wife Jane and family in Cornwall.

Crossing the isthmus of Nicaragua on foot

After leaving Cerro de Pasco, he passed through Ecuador on his way to Bogotá in Colombia. The party comprised Trevithick, Gerard, two schoolboys on their way to school in Highgate and seven natives, three of whom returned home after guiding them through the first part of their journey. The journey was treacherous - one of the party was drowned in a raging torrent and Trevithick was nearly killed on at least two occasions. In the first he was saved from drowning by Gerard, and in the second he was nearly devoured by an alligator following a dispute with a local man whom he had in some way offended. In Cartagena Trevithick met Robert Stephenson who was on his way home from Colombia. It had been many years since they last met when Stephenson was just a baby. Stephenson gave Trevithick £50 to help his passage home. He arrived at Falmouth in October 1827 with few possessions other than the clothes he was wearing.

Trevithick's return to England

Trevithick's later projects

Taking encouragement from earlier inventors who had achieved some successes with similar endeavours, Trevithick petitioned Parliament for a grant but he was unsuccessful.

In 1829 he built a closed cycle steam engine followed by a vertical tubular boiler.

In 1830 he invented an early form of storage room heater. It comprised a small fire tube boiler with a detachable flue which could be heated either outside or indoors with the flue connected to a chimney. Once hot the hot water container could be wheeled to where heat was required and the issuing heat could be altered using adjustable doors.

To commemorate the passing of the Reform Bill in 1832 he designed a massive column to be 1000 feet (300 m) high, being 100 feet (30 m) in diameter at the base tapering to 12 feet (3.6 m) at the top where a statue of a horse would have been mounted. It was to be made of 1500 10 foot (3 m) square pieces of cast iron and would have weighed 6000 tons. There was substantial public interest in the proposal, but it was never built.

Trevithick’s final project

About the same time he was invited to do some development work on an engine of a new vessel at Dartford by John Hall, the founder of J & E Hall Limited. The work involved a reaction turbine for which Trevithick earned £1200. He lodged at The Bull hotel in the High Street, Dartford, Kent.

Death

Efter at have arbejdet i Dartford i omkring et år, blev Trevithick syg af pneumonia og måtte holde sengen i The Bull hotel, hvor han boede på det tidspunkt. Following a week's confinement in bed he died on the morning of 22. april 1833. He was penniless, and no relatives or friends had attended his bedside during his illness. His colleagues at Hall's works made a collection for his funeral expenses and acted as bearers. They also paid a night watchman to guard his grave at night to deter grave robbers, as body snatching was common at that time.

Trevithick was buried in an unmarked grave in St Edmunds Burial Ground, East Hill, Dartford. The burial ground closed in 1857, with the gravestones being removed in the 1960s. A plaque marks the approximate spot believed to be the site of the grave.<ref>[http://www.dartford.gov.uk/cemeteries/easthill.htm Dartford Council, East Hill Cemetery page - Accessed 10 June 2008]</ref>

Conclusion

Professor Charles Inglis speaking in 1933 at a lecture to the Institution of Civil Engineers to commemorate the centenary of Trevithick's death included the following words:

„In the brief period between 1799 and 1808 he totally changed the breed of steam engines, from an unwieldy giant of limited ability he evolved a prime mover of universal application“.

One of his four sons, Francis, became Locomotive Superintendent of the Northern division of the London and North Western Railway.

Memorials

thumb|200px|Richard Trevithick's statue by the public library at Camborne, Cornwall Today, to commemorate his achievements, a statue depicting Richard Trevithick holding one of his small scale models, stands beside the public library at Camborne.

On 17th March 2007, Dartford Borough Council invited the Chairman of the Trevithick Society, Phil Hosken, to unveil a Blue Plaque at the Royal Victoria and Bull hotel (formerly The Bull) marking Trevithick's last years in Dartford and the place of his death in 1833. The Blue Plaque is prominently displayed on the Hotel's front facade and is clearly visible to visitors to the town.

The Cardiff University Engineering, Computer Science and Physics departments are based around the Trevithick Building which also holds the Trevithick Library, named after Richard Trevithick <ref>[http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/insrv/libraries/trevithick/index.html Trevithick Library<!– Bot generated title –>]</ref>.

Se også

Notes

References

- Lowe, J.W.,

British Steam Locomotive Builders(Guild Publishing, 1989) - Hodge, James,

Richard Trevithick(Lifelines 6 (2003), Shire Publications Ltd, Risborough, Buckinghamshire HP27 9AA UK). - Shelton Kirby, Richard et al.,

Engineering in HistoryDover Publications Inc., New York. ISBN 0-486-26412-2 - Rogers, Colonel H. C. OBE,

Turnpike to Iron Road(Seeley, Service & Co. Ltd. London 1961), pp 40 - 44. - Anthony Burton ,

Richard Trevithick: Giant of Steam(Aurum Press, London, 2000) ISBN 1-85410-878-6.

External links

Category:Richard Trevithick|Richard Trevithick

- [http://www.trevithick-society.org.uk/trevithick.htm Richard Trevithick 1771-1833] (a page from the Trevithick Society website)

- [http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RAtrevithick.htm Richard Trevithick on the Spartacus Educational website]

- [http://www.brooklands.org.uk/Goodwood/g9828.htm A replica of the

London Steam Carriagevisits Brooklands] - [http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/RApenydarren.htm The Penydarren Locomotive, on the Spartacus Educational website]

- [http://www.alangeorge.co.uk/PenydarrenLocomotive.htm Old Merthyr Tydfil: Richard Trevithick & Penydarren Locomotive] –

Historical Photographs of the Penydarren Locomotive - [http://www.fotocomboio.com/pt/Pessoas/Pioneiros/Richard_Trevithick.htm Portuguese written article about Trevithick]

- [http://www.trevithick-day.org.uk/ The Camborne ‘Trevithick Day’ Website]

- [http://www.dartfordarchive.org.uk/technology/engin_trevithick.shtml The Dartford Town archive]

- [http://www.cornwall-calling.co.uk/mines/harvey-hayle.htm The history of 'Harveys of Hayle']

- [http://crocat.cornwall.gov.uk/dserve/dserve.exe?dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqCmd=Overview.tcl&dsqSearch=((text)='richard%20trevithick') Cornwall Record Office Online Catalogue for Richard Trevithick]

- [http://camborne-old-cornwall-society.cornovia.org.uk/hist_accs/edmonds01.html Contributions to the Biography of Richard Trevithick - Richard Edmonds, 1859]

- [http://www.shimbo.co.uk/gallery/photo71.htm Bicentenary of Trevithick's 'Puffing Devil' run up Camborne Hill, 1801] –

(photo sequence) - [http://www.steamcircus.info www.steamcircus.info - Compilation of research on the exact location of Steam Circus and some new ideas]

<BR><!–blank line to separate links from navibox - please do not remove–> early-steam-locos

![Trevithick's No. 14 engine, built by [[John Hazledine|Hazledine and Co.]], Bridgnorth, about 1804, and illustrated after being rescued circa 1885; from Scientific American Supplement, Vol. XIX, No. 470, Jan. 3, 1885 Trevithick's No. 14 engine, built by [[John Hazledine|Hazledine and Co.]], Bridgnorth, about 1804, and illustrated after being rescued circa 1885; from Scientific American Supplement, Vol. XIX, No. 470, Jan. 3, 1885](/dokuwiki/lib/exe/fetch.php?w=250&tok=ffea0a&media=historie:trevithick_high_pressure_steam_engine_-_project_gutenberg_etext_14041.jpg)